| Traffic and road management |

| By Prof. Amal S. Kumarage |

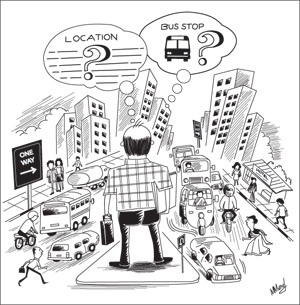

So we have heard of yet another experiment (extending the one-way flow from Vajira Road-Visaka) junction on Duplication Road to Dickmans Road (Lester James Peiris Mawatha) in traffic re-arrangement in Colombo? We have learnt to accept such ‘experiments’ to be successful since they are always implemented without debate or discussion. What we may not know is that there is no ‘before and after’ study, no survey on public perception, no consultation with other stakeholders and no cost benefit analysis. But who cares when there are no public complaints! Or so it seems! Many drivers who love to gun their machines on open roads love these one-way roads. Who would not? But wait! What about that bus passenger whose bus route and stop has now been moved to an entirely different road and who has to walk 10 minutes more each way to school or work? What about that pedestrian who now has to cross six lanes of traffic taking his life in his hand to test the skills of budding race drivers? What about the elderly who now need a three-wheeler just to cross Duplication Road? They too have been told it is a resounding ‘success’! Bus stops are incessantly moved about as the Police desires with scant consideration of the ease of passenger access. The many casualties that have occurred in attempts to cross these one-way roads are unknown to transport professionals and researchers, as the Traffic Police chief a year ago bluntly ruled that such information could be provided only to those who ‘need to know’. Alas, if there was only right of access to information we would have known! Traffic Management is a specialized and integrated function in many cities worldwide. It involves municipal traffic engineers, public transport regulators, transport operators, urban and transport planners, transport user groups and police officers. But in Colombo it seems that all these are rolled into one. Many may consider this approach as being progressive since finally something is seen to be happening. But is what is happening beneficial for all sections of society? Are the agencies that have been instituted by statute to provide for the different road user groups been ignored? For example, around 20,000 bus passengers including school children using Routes 104 and 154 after the last ‘successful’ one-way arrangement, have to daily detour five km for what used to be a trip of just one km down Bauddhaloka Mawatha. The passenger time loss alone due to this ‘success’ is a staggering Rs 2 million a week, which has continued for three years even though the road is now open for cars. Moreover, traffic studies have shown that the one-way traffic system in Galle Road/Duplication road, has led to higher congestion in areas such as Dehiwela and Kalubowila due to increasing diversions and on Baseline Road which has now become one of the slowest roads in the city during peak times. At Kohuwela it has been necessary to have even the central roundabout removed. On Dickmans Road and at Narahenpita area traffic levels have saturated. This is called traffic migration, where short sighted interventions only drive the traffic congestion from one place to another. It only benefits a few and inconvenience many. Roads are used by different people each one trying to get around to fulfill his or her own personal needs. Roads as public thoroughfares must ideally provide unfettered access. Thus congestion is an impediment and irksome to anyone. It costs us Rs 40 billion or more annually. No one wants it. Cities that cannot manage congestion are called chaotic and unlivable. In such cities congestion becomes the conversation starter and the excuse for running late for appointments and meetings. On an international level, congestion free travel is a quality of city life which attracts residents, investors and even tourists. One-way systems are usually part of an urban road system. They are successful when they form closely spaced loops like in grid iron type cross road systems seen in many newer cities. They are successful when the multiple users of roads including pedestrians get improved access and also improved mobility for all those in cars as well as in buses. Poorly designed one-way systems only appear to be successful. They may at best benefit a few motorists and cause extended journeys, delays, risks and casualties for the majority. They drive pedestrians and public transport users thus inconvenienced or endangered to stop walking or taking public transport and to use a car or motor cycle which in turn increases congestion in the long term. While the current initiative to revamp Colombo’s long neglected road system has to be appreciated by all, it bears the typical implications of rapid development that forgets sustainability of these measures and the less vocal pedestrian and public transport user. To add insult to injury those of us who travel only by car also forget that any speed we gain is often at the cost of delay to our colleagues, employees, clients, customers and students who travel by more sustainable modes of public transport and make equal contribution to make our city and its economy prosper. But even for a motorist it may be a false sense of ‘success’, with only the perception that he is travelling quicker to his destination when in fact he is not. One way traffic systems typically increase distances by 50%. So, if you were earlier travelling at 20 km/hour you now need to be travelling at say 35 km/hr to make it in quicker time. Longer distances also require more fuel even though there may be less idling due to fewer junctions. The Galle Road is now asphalt carpeted and redone with broad sidewalks. If the same investment was made when they were two-way, similar results could have been reached. But no study or appraisal is carried out to determine which is a better option or which set of roads should be made one-way or how bus routes and stops should be re-planned. There is no listening ear to introduce new technologies such as bus lanes or bus ways that would benefit the 60% of commuters to the city. There is no consultation with public transport authorities. There is no public debate. There is no invitation for experts or for professional opinion. There is no reference to existing studies or research on one-way systems. There is no traffic study based on origin and destination surveys. The administrators know it all and know best! The ‘new’ experiment on extending the one way southwards is bound to be yet another similar ‘success’. The inconvenience it will have on the users of bus Route No 112 or the thousands of school children in 8 or 9 schools in the area, especially those who walk or take public transport is unknown. What implications it will have on congestion on roads such as W.A. Silva (High Street), Dharmarama Road, Pamankade, Park Street and Thimbirigasyaya or Jawatte Roads have not been studied. This will also delink the important bus-rail transfer at Bambalapitiya, when south bound bus commuters will now have to walk all the way from Duplication Road to the station. Obviously this is to replicate the ‘success’ of the disintegration that has already happened at Kollupitiya station. But it is likely that the success of this experiment will be measured again only on the one fact that cars must travel faster- no matter who else suffers. Thus the public transport user whose mode of travel cause less congestion, less pollution, the poor, the elderly, the weak, the slow, they just have to get used to it or find other roads to travel on. The administrators are always correct and what they do is always a success and that is all the public needs to know. (Amal is a Senior Professor at the Department of Transport and Logistics Management at the University of Moratuwa and Sri Lanka’s foremost traffic management expert. He has served as the Chairman of the National Transport Commission and is currently the Chairman of the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport, Sri Lanka. He has also served as a transport advisor and consultant to governments and agencies in several South Asian countries). |

We are a concerned group of academics fighting to ensure the opportunity of high quality public higher education for the Sri Lankan masses. This blog is intended as a bulletin board to share news and ideas relevant to the cause. The views and opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the FUTA. If you wish to post any interesting articles please e-mail them to uteachers.sl at gmail.com

Sunday, July 17, 2011

What you should know about one-way traffic systems

The Sunday Times, 17/07/2011